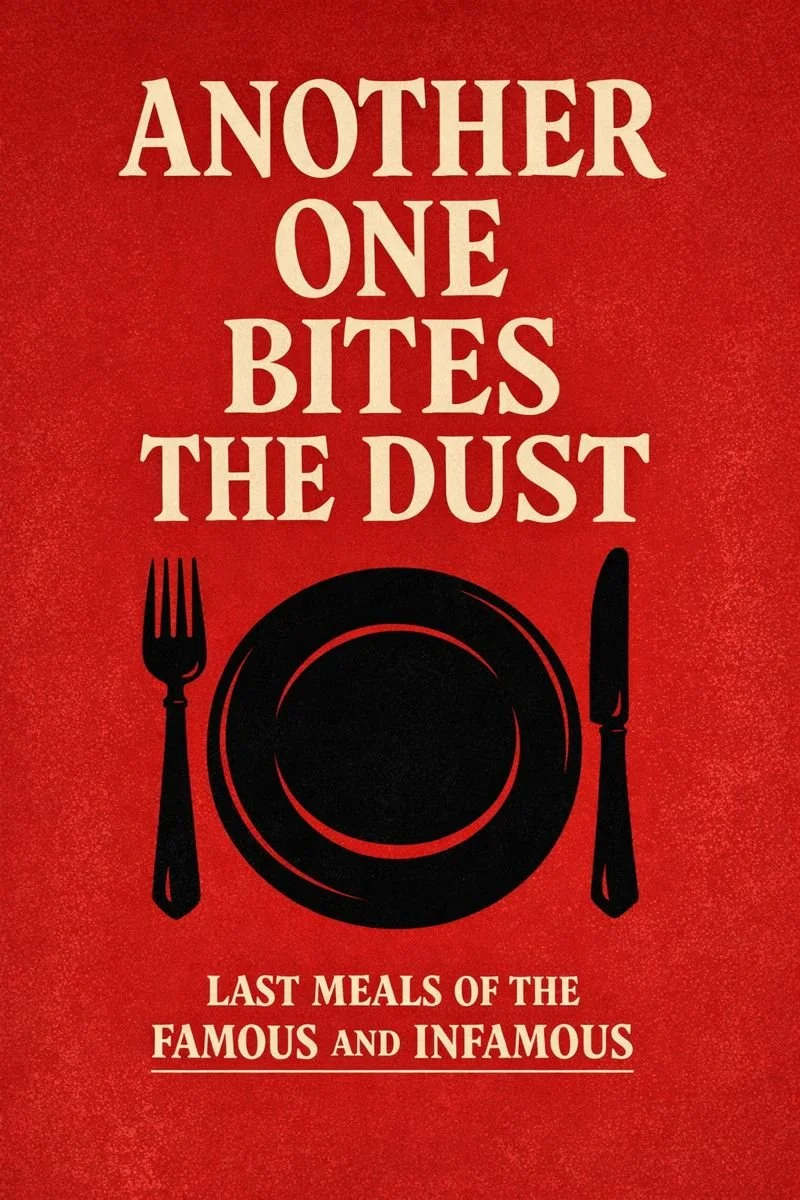

Dinner with Death

Everyone eats. Everyone dies. Sometimes in that order. Sometimes not.

Picture it: a man sits in a cell, the smell of greasy meat clinging to the air, as if a diner had set up shop in the shadow of the gallows. He cuts into his steak, chews slowly, savoring each bite like a condemned gourmand. Across town, a king drowns himself in wine and goose liver, convinced that the divine right of indigestion will keep the mob at bay. Somewhere else, a soldier gnaws on moldy bread in a trench, only to be interrupted by a shell that rearranges the menu. Different people, same outcome. The plate empties, the lights go out.

Meals are funny that way. They’re comfort. They’re ritual. They’re theater. They’re the last little act before oblivion. And we, the living, obsess over them like gossiping waiters: Did you hear what so-and-so had before the axe? A single olive, can you believe it?

The irony? The “last meal” says more about us than it ever does about the poor bastard eating it. We’re the voyeurs peeking through history’s kitchen window, fixated on whether the condemned man salted his fries.

The plate is a stage. The fork is a prop. The eater is already halfway gone. And we — the survivors, the spectators — lap it up.

So welcome. Sit down. The table’s set. You won’t need a reservation. You won’t need to tip. Just remember: dessert is always served last, and the bill will come whether you ordered it or not.